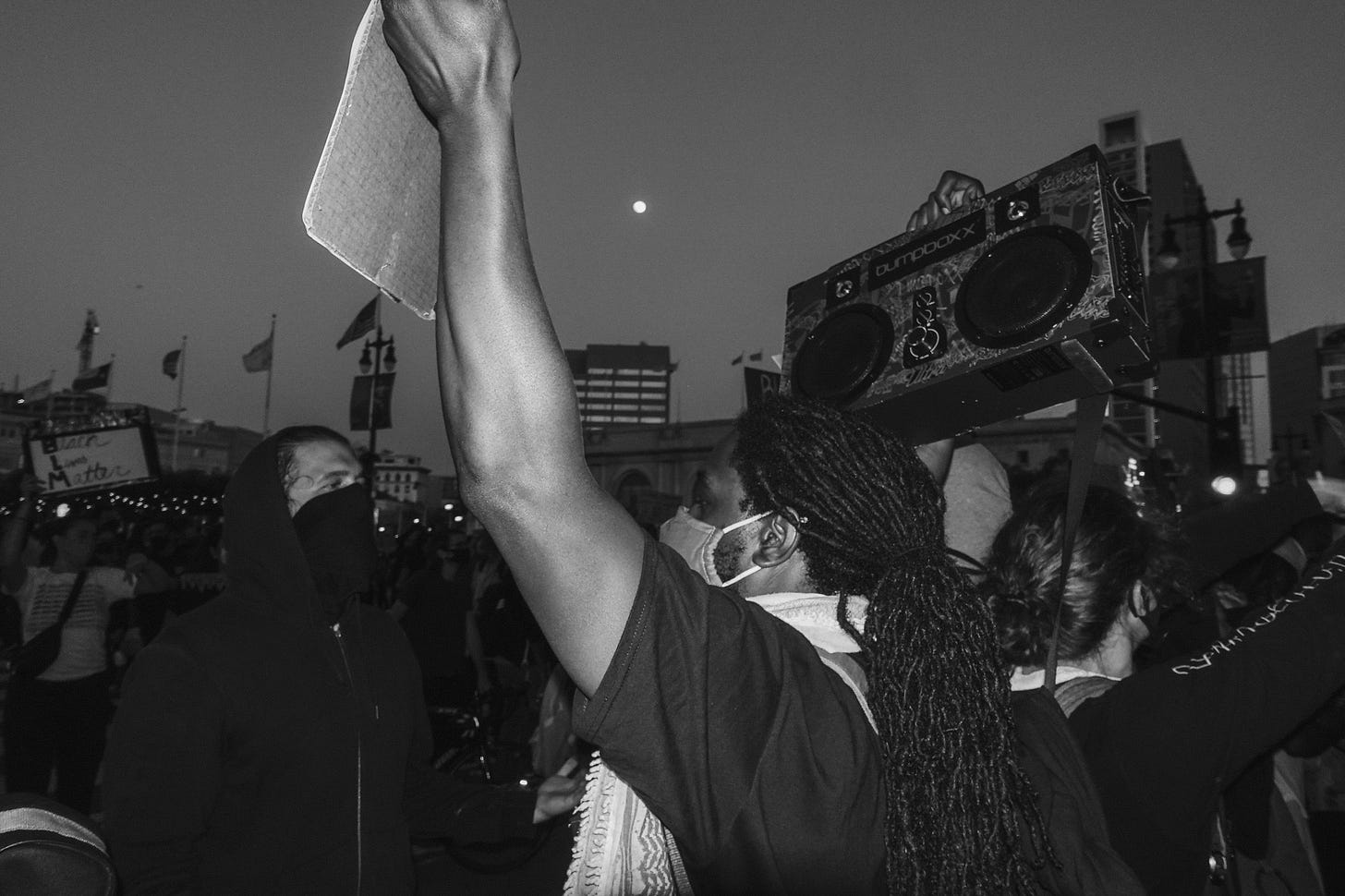

Protestor with boombox in a crowd of thousands protesting outside City Hall, June 03, 2020, San Francisco, CA

✉️ Letter—22.80

Hello architects,

Before I begin, I would like to preface by saying that I am no expert; I do not have any answers, and it is in no way my intention to take focus away from black narratives. But, as outcries reverberate across all fifty states and the globe, I believe it would be remiss of me to not speak up. I dedicate this volume to furthering my understanding of what it means to stand in solidarity—how to listen and how to learn.

In the wake of events these past few weeks, I’ve had to step away from the ever-flowing stream of social media; to collect my thoughts.

In these moments, I sit with two versions of myself—present and past, to ask, wholeheartedly, what it means to stand in solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement. As an Asian-American, this starts by looking at my own biases.

As COVID-19 spread across the country, our communities grounded to a halt. And just as it’s easier to focus on an object at rest, the stillness made us see our nation’s greatest disparities. Black Americans were disproportionately affected by the health crisis and Asian Americans increasingly became targets of hate crimes. It became frustratingly and shamefully clear that the “model minority myth” not only failed to protect any of us in times of uncertainty, but that white institutions have always weaponized it to propagate anti-blackness. In The Color of Success, Ellen Wu, Associate Professor at the Indiana University Bloomington, adds the following color to this idea:

The backdrop of the growing Civil Rights movement in the 1960’s caused white Americans to double down on the model minority myth, as “proof that the right kind of minority group could achieve the American dream,” on their own and without support. “The insinuation was that hard work along with unwavering faith in the government and liberal democracy as opposed to political protest were the keys to overcoming racial barriers as well as achieving full citizenship.”

These disparities, though more visible now, have long existed. I don’t want to focus on my narrative here, but I wish to recognize one aspect. As a previous member of a predominantly Asian hip-hop dance crew, I’ve cherry-picked elements from black culture—particularly hip-hop dance and music—for my own benefit without a proper appreciation for the culture. It provided me with community, expression, joy, and I can no longer atone for that kind of complicity. Going forward, I will also call out such cases in myself and others around me.

James Baldwin famously said, “Not everything that is faced can be changed. But nothing can be changed until it is faced”, and I believe such is true for the self.

Before we can listen and self-educate effectively, we must create the capacity for it. The outflow of donations, pre-drafted e-mails, and antiracist curricula across social media is awe-inspiring, but without space within ourselves to listen, I frankly cannot disassociate viral hashtags and two-click-solidarity from performance. The notion that we can earn solidarity through an activism laundry list is a dangerous oversimplification of the issue, and it begs the question: when there is no audience, how can we ensure our values remain resilient?

On the pendulum of either engulfing one’s self in social media or taking a step back for mental clarity, I have benefited and am learning from the latter. I encourage my fellow non-black readers to use that time to face one’s past complicity—seeking not an absolution of guilt, but a greater capacity for compassion that equips us to take action within our locus of control—who we influence, what we consume, how we spend our money—with sincerity. For therein lies, as it always has, our fundamental responsibilities to seek discomfort, to consider the invisible forces at play, and simply, to just be decent.

In solidarity,

Brandon

🧠 Curiosity—The American Nightmare

“We don’t see any American dream,” Malcolm X said in 1964. “We’ve experienced only the American nightmare.”

In 1896, a statistician named Frederick Hoffman published Race Traits and Tendencies of the American Negro, a disturbing compilation of statistics and eugenic theory. Through his research, Hoffman looked to confirm a twisted hypothesis: that white Americans were naturally selected for life, while black Americans were naturally selected for “gradual extinction”. In The American Nightmare, Director of the Antiracist Research and Policy Center at American University, Ibram X. Kendi analyzes the implications of this text, and how injustices today stem from such ideologies.

Hoffman’s work received notable critiques from W.E.B. Du Bois and, mathematician, Kelly Miller, claiming Hoffman used an “unscientific use of the statistical method”. One example is that while Hoffman had used crime data, racial health disparities, and mortality rates against blacks, he refused to stratify his data based on social or economic status. By keeping the data aggregate, he obscured any potential causal relationships beyond one based on race (Wolff).

Yet, Hoffman would achieve the validation he desired after publishing it in the Journal of the American Economic Association, where his work was met with positive reception. This piece would go on to propel Hoffman’s career, to what his biographer described as “the fulfillment of the ‘American Dream’”.

Enter Kendi’s metaphor of the nightmare: “to be black and conscious of anti-black racism is to stare into the mirror of your own extinction.”

For the remainder of the article, Kendi elaborates on how the injustices today stem from generations of the same institutionalized racism once championed as the “American dream” over a century ago.

From the regard for Hoffman’s work as “the most influential race and crime study of the first half of the twentieth century” from his supporters to the fact that Minneapolis police, mind you, one of the most progressive in the country, is “13 times more likely to kill black residents than to kill white residents”, Kendi’s analysis is as haunting as it is well-researched. One does not need to go much further to accept that things happening today are not isolated events. They fit into a larger pattern.

In a nation where we are taught many “universal truths and privileges”, where we pledged allegiance every day to the ideals of liberty and equal opportunity, it is shameful that we must still clarify by asking “for whom?” It is more critical than ever to question the biases we’ve long accepted.

As we continue our dialogue with others, I would like to leave with a statement towards the end of Kendi’s piece:

Either there is something superior or inferior about the races, something dangerous and deathly about black people, and black people are the American nightmare; or there is something wrong with society, something dangerous and deathly about racist policy, and black people are experiencing the American nightmare.

In conversations lately, I often hear all sorts of rebuttals against looting; against defunding police; against liberal idealism, as though both sides of the discussion exist on different planes, and perhaps that’s because they are.

For more effective conversations on this topic, consider starting with these two explanations. Then, we are left with two cases—either the person is deeply racist or the person is simply misinformed. For the latter, it becomes a matter of actively listening and reflecting, understanding that it’s possible to validate someone’s feelings without agreeing with them. I admittedly need to work on this, but as divisive as they may appear, these conversations may help us all start dreaming American again.

🎨 Curated—Ally & Amplify

As we seek to educate ourselves offline, let us remind ourselves that antiracism is not a virtue race. There is no prize for the first person to finish an antiracism reading list. Let the resources guide you and remember it is nobody’s responsibility to educate yourself on this topic but your own. It’s a privilege to be able to take a step back from the issue, so please do so as needed while we pursue long-term learning.

On reading lists, assistant professor of English and African American Studies at Northwestern University, Lauren Michele Jackson writes:

For such a list to do good, something keener than "anti-racism" must be sought. The word and its nominal equivalent, "anti-racist," suggests something of a vanity project, where the goal is no longer to learn more about race, power, and capital, but to spring closer to the enlightened order of the antiracist. And yet, were one to actually read many of these books, one might reach the conclusion that there is no anti-racist stasis within reach of a lifetime. Thus there cannot be an anti-racist canon that does not crystallize the very sense of things it proposes to undermine. The very assurance of absolution is tainted… But it is unfair to beg other literature and other authors, many of them dead, to do this sort of work for someone. If you want to read a novel, read a damn novel, like it's a novel.

Ally

Anti-racism Resources by Sarah Sophie Flicker & Alyssa Klein

For one of the most thorough and organized lists of anti-racism resources I’ve seen.Letters for Black Lives

For Asian-Americans looking to have a conversation with their family on the matter.defund12

For pre-drafted emails to local government officials and council members to reallocate egregious police budgets towards education and social services.

Amplify

“13TH”

For an eye-opening and heartbreaking documentary on the U.S. prison system and the effects of our nation’s deeply entrenched systemic racism on crime and incarceration.“We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black. But by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt their communities.” – John Ehrlichman, Assistant to the President for Domestic Affairs under President Nixon

“Martin and Malcolm”

For James Baldwin’s account of two of the most influential activists from the Civil Rights era. I plan to read more of Baldwin’s body of work soon.“By the time each met his death, there was practically no difference between them.”

Wale - Sue Me (feat. Kelly Price)

For a moving conceptual music video depicting an alternative American reality where our racial biases are flipped.“Sue me, I’m rooting for everybody that’s black.”